Well, this is going to be a great story, I thought.

I was in Denver’s Mile High Stadium, and it was August 12, 1993. Ninety thousand young people from all across the globe, worked up to a fever pitch, erupted with thunderous cheers as they first spotted their hero: Pope St. John Paul II, just arrived to open World Youth Day officially.

My wife, Joan, was nearby with a group of Catholic young people from Scottsbluff and Gering, Nebraska, where we lived and worked at the daily newspaper. She was there as a participant, a cradle Catholic taking advantage of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see her spiritual leader. I was plying my trade.

I jotted down impressions in my notebook as John Paul toured the stadium, then began his greetings to the numerous nations represented in Denver. Nothing unexpected for a world leader, I thought, as the Pope began greeting the non-Catholic Christians in the audience.

“Most of you are members of the Catholic Church, but others are from other Christian churches and communities, and I greet each one with sincere friendship,” he said. “In spite of divisions among Christians, ‘all those justified by faith through baptism are incorporated into Christ … brothers and sisters in the Lord.’ ”

The Holy Father shook up my life in that moment. It may be difficult to understand why … unless you’ve grown up Lutheran.

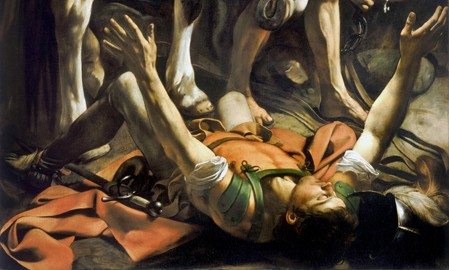

I had just heard a statement echoing the key battle cry of the Reformation, the one cited by Martin Luther and all Lutherans after him as the doctrine on which the Church stands or falls: “For by grace you have been saved through faith; and this is not your own doing, it is the gift of God — not because of works, lest any man should boast” (Eph 2:8–9).

And it had come from the Pope: the successor of the man who had excommunicated Luther nearly five hundred years before. Well-versed Catholics will recognize that John Paul merely quoted Unitatis Redintegratio, the Decree on Ecumenism from Vatican II. But I didn’t know that. It was one of many things I didn’t know — one of many things I wouldn’t have believed only a few years before.

My mind raced back nearly six years to the day, back to the rectory at St. Agnes Catholic Church in Scottsbluff. I thought I wanted to marry Joan, but I had to be sure. I asked my most burning question point-blank to her pastor, Father Robert Karnish: “What is the way salvation is obtained?”

Without hesitation, Father Bob answered: “Faith in Jesus Christ, which is totally unmerited by us.”

His answer backed up what Joan had been telling me — that she believed what I did when it came to justification. Because he answered that way, I stood before him to marry Joan a few months later.

And because the Holy Father said what he said at that moment in Denver, God eventually led me into the Catholic Church.

Scenes from a Journey

Every life’s journey has its key scenes, its watershed events that set the course for all that follow them. Mine were placed roughly at five-year intervals from my confirmation in my native denomination, the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod (LCMS), on April 2, 1978, to my reconciliation with Rome on March 29, 1998.

To be specific, just five scenes form the backbone of my journey into the Catholic Church. My heart and mind are full of thoughts; my bookcase is bulging with books and magazine articles that multiplied as the journey went on. I could easily fill a special newspaper section — if not a full-length book — with the things that seem absolutely essential to understand how this born, bred and convicted conservative Lutheran ended up in the Catholic Church!

But throughout these five scenes, the issue of justification was there all the time. If you grow up in the LCMS and really believe what it teaches, it can’t be otherwise. Of all the thousands of Protestant denominations, few are more dedicated than the Missouri Synod to preserving the original arguments with Rome — especially when it comes to justification, the article on which Luther said the Church stands or falls.

To Catholics then and now, the key issue in the Reformation is authority: Luther’s rejection of the doctrinal authority of the pope and the Magisterium of the Church. And, indeed, the continuing rejection of that authority is very important to Lutherans. But it’s not the first issue they talk about.

Justification comes first — for Luther and the Reformers couched every disagreement in terms of their conviction that the Catholic Church doesn’t believe that salvation comes through Christ’s free gift, but from performing this sacrament, that rite, this prayer to Mary, that indulgence.

Almost any spiritual journey from Wittenberg to Rome (especially if it detours through Missouri) hinges totally on that conviction. Unless Lutherans perceive common ground with Catholics on justification, Catholics can’t hope to get Lutherans to listen to the Church’s views on authority, Mary and the saints, purgatory, and indulgences and the sacraments, especially the Eucharist. Unless the cornerstone of Lutherans’ mighty fortress against Rome is removed, the rest of the wall won’t fall.

Let’s go back to the place where my fortress was built.

Scene 1: “We Knew What Was Right”

I recall being in a classroom in 1978 in a Lutheran school in western Nebraska, not too long before my confirmation. My pastor drew a diagram on a chalkboard to outline the differing beliefs about what happens when the Words of Institution are spoken in the Eucharist.

The Catholic section of the diagram said only “body” and “blood”; the Protestant section, “bread” and “wine.” The Lutheran one linked “bread” to “body” and “wine” to “blood,” showing Luther’s belief in Christ’s Real Presence “in, with, and under” the bread and wine. Catholics believe in transubstantiation, Pastor said; Protestants believe the Eucharist is only a symbol. Both were wrong; Luther was right. This is where our synod stands.

Missouri is big on taking stands. The synod’s founders were Saxon Germans who immigrated to America in 1839 rather than submit to the forced union of Germany’s Lutheran and Reformed (Calvinist) state churches. The first LCMS president, the Rev. C. F. W. Walther, firmly believed in the doctrines espoused by Luther and his fellow German Reformers, especially as expressed in the Lutheran Confessions — the doctrinal statements adopted by Lutherans in the 1580 Book of Concord.

Walther’s beliefs have been enshrined in the Missouri Synod since its founding in 1847. Article II of the LCMS Constitution makes it crystal clear what every member congregation must uphold: “the Scriptures of the Old and the New Testament as the written Word of God and the only rule and norm of faith and of practice” and the Lutheran Confessions “as a true and unadulterated statement and exposition of the Word of God” (emphasis added).

That constrains Missouri’s members to stand firm against all who believe otherwise — even if they’re in another Lutheran church body, even if they’re part of the LCMS itself. During my childhood (I knew nothing of this before college), most of the faculty and students of the synod’s flagship seminary in St. Louis walked out in 1974 after a majority of delegates to the previous year’s LCMS convention declared they were drifting too far from Missouri’s historic course and too close to liberal theology and its denial of scriptural authority. (A number of congregations followed them out and eventually joined two larger church bodies in the 1988 formation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.)

These beliefs also commit the LCMS to the German Reformers’ litany of objections to the Catholic Church’s teachings: Catholics believe salvation depends on your works; they place the pope above the Bible; they pray to Mary and the saints; they believe in purgatory; they accept seven sacraments, not two; and, of course, they insist on this “magic show” called transubstantiation.

I absorbed all these objections, along with the absolute emphasis on justification by grace through faith as the chief cornerstone of Christianity. Christ died on the cross to save us from our sins. We’re born sinful; there’s nothing we can do to earn salvation. We are saved only through God’s free gift of faith through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. And we need that free gift throughout our lives, for the Christian is both saint and sinner — always prone to fall into the trap of believing he or she can make it to heaven without God’s help.

There was no doubt whatever in my mind about it; indeed, no one in my family doubted it. My Danish maternal grandmother summarized it best when recalling her own childhood a century ago: “We knew what was right, and it never occurred to us to do otherwise.”

Which only more strongly poses the question: Given my background, how on earth could I end up Catholic?

On one level, the answer is easy: It was God’s grace. More to the point, He preserved me from the depth and intensity of the Missouri Synod’s official feelings regarding the Catholic Church. For if you believe the Confessions are drawn from God’s Word, you also commit yourself to believing “the pope of Rome and his dominion” (to quote a 1932 LCMS doctrinal statement) are the Antichrist: Luther’s incendiary charge against those who threw him out of the Church.

That simply wasn’t part of my training. Young Missouri Synod Lutherans aren’t taught the entire contents of the Lutheran Confessions. They are expected to read and master Luther’s Small Catechism, which certainly includes the key elements of Lutheranism: the stress on justification, the views on the Real Presence. But you won’t find the word “Antichrist” — or any anti-Catholic polemics — anywhere in it.

Though my pastor taught the theological differences with Rome, he didn’t teach the polemics, and he didn’t call the pope the Antichrist. And the standard LCMS confirmation vow requires a new member to confess belief in Lutheran teachings “as you have learned to know it in the Small Catechism,” not the Confessions as a whole.

So I didn’t carry all the anti-Catholic baggage into life as an adult Lutheran. But I believed the Missouri Synod’s take on Rome’s beliefs as firmly as Luther ever did.

Scene 2: Once Saved, Always Saved?

Fast-forward a few years to 1983. I was alone in a hotel room in Germany on the Fourth of July, the last day of a five-week tour with my LCMS college choir in honor of Martin Luther’s five-hundredth birthday. I was paging through my Bible, writing in my diary, looking for answers to reconcile what I believed about justification with what I’d witnessed among our group.

I had entered that school a year before with the intention of becoming a music teacher in LCMS high schools. The European tour changed my life. We sang in beautiful cathedrals, drank in the sights of our ancestral land and even sang a surreptitiously scheduled concert behind the Iron Curtain in a tiny, embattled church in Leipzig in what was then East Germany.

Those were the high points. They weren’t why I was in that room.

Several of the choir members — people planning to be pastors, teachers, church musicians — largely abandoned the pretense of consistently living their faith while they were so far from home. Some of them drank to excess, which didn’t help. But they also ridiculed those who suggested they weren’t setting a good example.

And the leadership of the choir, all too often, sided with them.

We were all young; I know I didn’t handle my own reactions as well as I should have. But the experience shattered my beliefs about who we were and what we were supposed to be doing. It wasn’t that I expected people not to sin; I learned my confirmation lessons too well for that. But these ministers-in-training not only were sinning … they didn’t seem to care.

So there I was, trying to make sense of what had happened, asking myself: Was I wrong? I found myself in Paul’s letter to the Romans, the epistle Luther used more than any other in building his theology of justification.

“What shall we say then?” Paul wrote in Romans 6:1–2. “Are we to continue in sin so that grace may abound? By no means! How can we who died to sin still live in it?” He emphasizes and expands on the point in Romans 8:9: “But you are not in the flesh, you are in the Spirit, if the Spirit of God really dwells in you. Any one who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to Him” (emphasis added).

Then, in Romans 8:12–14, Paul lays it on the table for Christians who are tempted not to live the life to which Christ has called them:

So, then, brethren, we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live according to the flesh — for if you live according to the flesh you will die, but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body you will live. For all who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God.

I wasn’t wrong. Here was the proof in the Scriptures. We can’t sin without consequences, even after we’ve been justified by grace through faith. God expects His people to shine their lights all the time, not just during the concert; to live their faith at all times, not put it away when it’s time to have fun. To do otherwise — to sin and not care — is to throw away that undeserved gift of grace through faith in Christ.

At the time, that discovery saved me from total disillusionment in my Lutheran faith. It also started me down the road toward the Catholic Church — though it would be years before I understood how important, both personally and theologically, that moment would be.

I came home deeply conflicted about God’s plan for me. I didn’t think I could function in a ministry that appeared to tolerate such a gap between belief and practice. Then, quite unexpectedly, I got a call from the publisher of my hometown newspaper, for which I had written a column on high school activities. He wanted me to fill in for the rest of the summer for a sports editor who had suddenly quit.

I enjoyed it and found my niche. And after I returned to college that Fall, opportunities in journalism kept coming my way without my asking for them. After a month, I decided God was giving me a different mission. I transferred at semester’s end to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL), home to one of the nation’s best journalism programs. I’ve been a journalist ever since.

Scene 3: “That All May Be One”

Less than five years later, on May 28, 1988, I stood before a Catholic altar on my wedding day. Not only had God yanked my professional life in a different direction; He had sent me my life’s partner from the most unexpected of directions.

My three years at UNL had been everything I hoped for — in every area but one. I was fortunate to land in an LCMS campus ministry full of young people who lived their faith amid the admittedly more hostile atmosphere of a secular university. I wrote for and eventually edited the ministry’s monthly newsletter when I wasn’t studying or writing for the main UNL campus newspaper, the Daily Nebraskan.

But I had hoped for, tried for, and frankly embarrassed myself in the quest to find a woman to share my life. Simply put, I crashed and burned. My last hope among the women I met at UNL faded for good soon after I left for my first job in North Platte, Nebraska.

Or so I thought.

Quite unexpectedly, a friendship with my copy desk chief at the Daily Nebraskan, Joan Rezac, began to blossom. I nearly missed the signals when she started hinting she was interested in something more, but I came to my senses just in time. On April 5, 1987, I asked her on the phone: “Are we moving beyond a friendship?”

“I’m glad you called,” she said. “The thought had crossed my mind!”

Right then, I knew — absolutely knew — the search was over. I can’t explain why, and I didn’t tell Joan until much later. But the phone calls and trips back to Lincoln for dates proved it. Here was a fellow journalist who loved music and seemed to understand me better than anyone ever had.

I can’t do justice in this short space to how perfectly Joan fit into my life, other than to say I’ve never doubted in the years since that phone call that she was, and is, God’s precious gift to me. But she was Catholic. Catholic.I’ve never doubted in the years since that phone call that she was, and is, God’s precious gift to me. But she was Catholic. Why, God? Why did you send me a Catholic? This surely can’t work … can it? Share on X

Why, God? Why did you send me a Catholic? This surely can’t work … can it?

We started working on the answer only a few weeks into our relationship. I gave her a copy of Luther’s Small Catechism, while she gave me a Catholic catechism she had studied in her confirmation class. Naturally, as a good Missouri Synod Lutheran who knew Catholics were wrong, I figured I had the tools to wake Joan up. If we were to have a future as a couple, I had to.

And I tried hard and long during those first few months. There was only one problem: It made her a stronger Catholic. And I was the one who had to adjust.

I attended church with her occasionally, heard the Mass in the vernacular, saw Communion given in both kinds. She told me how Vatican II had broadened the Church’s approach to other faiths. I read that Catholics were finding that Luther’s teachings weren’t as un-Catholic as they had thought. And on justification? Joan said she believed that works, while they don’t save us, let our faith shine through.

In other words, this Catholic Church was … so to speak … more Lutheran than I imagined. It was my first clue that I had been viewing Rome through a distorted mirror — the one held up by my confirmation instruction. Though Vatican II had happened a decade before that, the Rome that I was taught as a young Lutheran was the Rome of 1517 — at least in the way Rome presented itself at that long-ago time. Something was different.

I could not escape that fact as Joan and I debated the spiritual issues that summer of 1987. It wasn’t an easy ride, to be sure. Sometimes it seemed that Joan and I were speaking different languages. I certainly didn’t believe all that stuff about Mary, the saints, purgatory and the sacrifice of the Mass, though I was hearing things here and there that gave me pause.

But we came through that time closer than ever. And Father Karnish’s straight answer to my straight question about justification helped convince me that Joan and I could function as a Christian couple. If the priest who helped form Joan’s faith was saying the same thing she was, we could grow in faith together as husband and wife.

Even so, finding some points of agreement with Catholics wasn’t enough for me to become one, though we did get married at St. Agnes. We resolved to attend each other’s churches regularly, minister together where we could and let God tell us whether He wanted us to join one or the other or remain in both. I needed more proof that the Catholic Church I was hearing about from Joan and Father Karnish was the Church that really existed.

It took me ten years to be convinced.

Scene 4: The Surprising Pope from Poland

The moment in Denver in 1993 when I heard those astonishing words from the Pope happened almost halfway in between those ten years. It came at a time when our marriage was full of spiritual blessings and professional challenges. But it seemed that we were destined to be a two-faith couple.

Joan had taken Lutheran confirmation classes in Des Moines, where we moved after our marriage. But she just wasn’t inspired to join. Something would be missing, she said — something she couldn’t put into words. So after we moved to Scottsbluff in 1991, I entered an RCIA (Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults) class at St. Agnes, intending to stop before the point that I would have to commit myself to join.

Again, I was surprised at the level of agreement I was finding between the two faith traditions. I remember thinking that I could be comfortable at St. Agnes. But something kept gnawing at me. You see, I had started RCIA instruction in Des Moines, but left after two weeks. That priest seemed to doubt the essence of Christian faith: Catholic, Lutheran, or otherwise.

So I asked St. Agnes’ new pastor, Father Charles Torpey: Could he guarantee me that I would hear the same message about the Catholic faith in another parish or another diocese?

No, he said.

He was merely reflecting the varying interpretations of Vatican II that have plagued the Church for most of the years since the Council. But for me, at that time, Father Torpey’s answer stopped me cold.

I was used to hearing pretty much the same Lutheran doctrines from one Missouri Synod congregation to the next. Even though I was comfortable with what Joan believed, her family believed and her parish believed, without the guarantee I sought, I simply assumed the Catholic Church as a whole couldn’t possibly believe as they did.

A year later, John Paul II shook up that assumption in Denver.

As Joan and I had our second child and then moved back to North Platte, the Pope kept doing things I couldn’t ignore. The year after World Youth Day, the Vatican released the English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Though I didn’t read it cover to cover until after I joined the Church, its release was a profound event — the beginning of order from the chaos of the varying interpretations of Vatican II.

Then John Paul issued Ut Unum Sint, the great 1995 encyclical on ecumenism in which he urged Protestants and Eastern Orthodox alike to join Catholics in restoring the Church’s unity. A year later, the Holy Father went to Paderborn, Germany, and directly urged Lutherans and Catholics to look at the complete picture of Luther and the Reformation and approach their five-hundred-year feud in a different way. Addressing an ecumenical audience at the Paderborn Cathedral, he observed:

Luther’s thinking was characterized by considerable emphasis on the individual, which meant that the awareness of the requirements of society became weaker. Luther’s original intention in his call for reform in the Church was a call to repentance and renewal to begin in the life of every individual.

There are many reasons why these beginnings nevertheless led to division. One is the failure of the Catholic Church … and the intrusion of political and economic interest, as well as Luther’s own passion, which drove him far beyond what he originally intended into radical criticism of the Catholic Church, of its way of teaching.

We all bear the guilt. That is why we are called upon to repent and must all allow the Lord to cleanse us over and over.

After nearly a decade of study and close observation of Catholicism, I could take the Pope’s words and sentiment for what they were. The messages I first heard in 1987 had been confirmed week in and week out from Catholic pulpits. I had absorbed the wonderful liturgical music coming from Catholic composers. I prayed for unity in God’s Church more strongly than ever.

And yet … I remained confirmed in my Lutheran thinking. When it came to Mary, the saints, purgatory and so on, I had searched in vain for a response to Luther’s ancient challenge: Prove it to me from Scripture!

In mid-1997, we moved to Omaha. As always, I started looking for an LCMS congregation to join. I found one I thought I liked: one that did contemporary music, one that had people I had known from other parts of Nebraska. But something wasn’t right. Something kept gnawing at me, preventing me from becoming an official member of the congregation. I didn’t know what it was.

That Christmas, we received a gift from Sister Mariette Melmer, a cousin of Joan’s mother and a Notre Dame sister based not far from our new home. (The Lord called her home in August 1999.) She told Joan she thought we would find it interesting. Joan started reading the book, then passed it on to me. It was Rome Sweet Home, Scott and Kimberly Hahn’s story of their journeys from a Presbyterian denomination into the Catholic Church.

It wasn’t a perfect fit; I was a Lutheran reading an ex-Calvinist’s conception of what Luther believed. And yet … here were all these Scripture passages addressing the differences between Lutherans and Catholics. Hahn was pointing to Scripture. And he was making sense. For instance, his connection of purgatory to passages I had never paid attention to before, such as 1 Corinthians 3:12–15:

Now if any one builds on the foundation [of Christ] with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw — each man’s work will become manifest; for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each one has done. If the work which any man has built on the foundation survives, he will receive a reward. If any man’s work is burned up, he will suffer loss, though he himself will be saved, but only as through fire.

As so many ex-Protestant converts have said … I knew I was in trouble. It was time to answer the questions once and for all.

I was driven by something the pope had written in Ut Unum Sint:

In the first place, with regard to doctrinal formulations which differ from those normally in use in the community to which one belongs, it is certainly right to determine whether the words involved say the same thing . . ..

In this regard, ecumenical dialogue, which prompts the parties involved to question each other, to understand each other and to explain their positions to each other, makes surprising discoveries possible. Intolerant polemics and controversies have made incompatible assertions out of what was really the result of two different ways of looking at the same reality. (38)

I couldn’t pass up that challenge. It called on skills I use all the time as a journalist: the translation of the jargon of doctors, lawyers, school administrators, and others into language common people can use. After ten years of virtual dual membership in the Catholic Church and the LCMS, I believed I knew both sides’ theological languages well enough to test it.

The twenty-year journey was entering its final phase.

Scene 5: Amid the Crumbled Fortress

Just over a month later, on February 1, 1998, I stood over the dishes in the sink, looking out at the winter night. The tears kept coming. I knew I had run out of arguments. The walls of my mighty Lutheran fortress lay in ruins around my feet. I knew I had to become Catholic.The tears kept coming. I knew I had run out of arguments. The walls of my mighty Lutheran fortress lay in ruins around my feet. I knew I had to become Catholic. Share on X

I was nearing the end of the second draft of what had become a forty-page paper, a conversation with myself about my journey. I had pored through Internet pages, haunted the libraries of our city and a nearby Catholic university, and raided bookstores in my quest.

The Pope had been right. On several critical issues, Lutherans and Catholics indeed said the same thing in different ways. With others, it had been less a matter of giving up Lutheran beliefs than coming to understand how Catholic they really were. And with the rest — Catholics simply had the more convincing case.On several critical issues, Lutherans and Catholics indeed said the same thing in different ways... . And with the rest — Catholics simply had the more convincing case. Share on X

Naturally, justification was the first issue. As I sorted through a decade’s worth of evidence, I found I had no doubts left: On this most important issue, Lutherans and Catholics were arguing over style — not substance. And after five hundred years of diatribes by both sides, both faith traditions are beginning to understand that at last!

Over time, I had come to understand that two questions govern our lives as Christian believers: “How are you saved?” and “Okay, you’re saved — now what?” The first refers to the moment and means of salvation; the second, to our spiritual journey from the moment of salvation until death. Just as Paul did throughout Romans, we must ask and answer both questions together to understand the entire picture of salvation.

Lutheran sermons typically focus on the first question, while Catholics concentrate on the second. Consequently, each thinks the other doesn’t answer the key question. Lutherans assume Catholics believe our totally undeserved gift of God’s grace is not the sole means of our salvation. Yet the very beginning of the Council of Trent’s Decree on Justification freely confesses our utter dependence on God:

If anyone shall say that man can be justified before God by his own works which are done either by his own natural powers, or through the teaching of the Law, and without divine grace through Christ Jesus: let him be anathema. (Canon 1)

If anyone shall say that without the anticipatory inspiration of the Holy Spirit and without His assistance man can believe, hope and love or be repentant, as he ought, so that the grace of justification may be conferred upon him: let him be anathema. (Canon 3)

For their part, Catholics assume that “faith alone” means Lutherans believe that “once saved, always saved.” Paul didn’t believe that, as we have seen. Christ didn’t teach it, either, as we see in Matthew 7:21: “Not every one who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of My Father who is in heaven.”

We are totally dependent on God for our salvation, Catholics teach, but we can throw it away. How? By willfully returning to a life of sin and assuming we’re saved anyway! Thus the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches: “Mortal sin … results in the loss of charity and the privation of sanctifying grace, that is, of the state of grace. If it is not redeemed by repentance and God’s forgiveness, it causes exclusion from Christ’s kingdom and the eternal death of hell” (1861).

So … do Lutherans believe you can throw your salvation away? The Lutheran Confessions say yes! One of the most unequivocal statements to that effect can be found in the “Apology” of the Augsburg Confession, where Luther’s right-hand man, Philip Melanchthon, writes about Paul’s statement that “if I have all faith so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing” (1 Cor 13:2):

In this text Paul requires love. We require it, too. We have said above that we should be renewed and begin to keep the law, according to the statement (Jer 31:33), “I will put my law within their hearts.” Whoever casts away love will not keep his faith, be it ever so great, because he will not keep the Holy Spirit. (Apology, IV, 219, in The Book of Concord, ed. Theodore G. Tappert et al., Fortress, 1959; emphasis added)

Related thoughts elsewhere in The Book of Concord may be found in the Augsburg Confession, VI, 1–2; the Apology, IV, 348–350; XX, 13; the Smalcald Articles, III, III, 42–45; and the Formula of Concord, Epitome, III, 11.

Now we’ve reached the common ground. Recall that many English translations render the “love” of 1 Corinthians 13:13 (“So faith, hope, love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love”) as “charity” (in Greek, agape; in Latin, caritas). Charity is an active love of both God above all things and our neighbor as ourselves; as such, it’s considered by Catholics as the greatest of the “theological virtues” (which also include faith and hope). This is what following through on our faith — the Catholic concept, much maligned by Lutherans, of “faith fashioned by love” — is all about.

Lutherans speak of these issues under another name: the “third use of the Law,” as found in the 1580 Formula of Concord:

The law has been given to men for three reasons: (1) to maintain external discipline against unruly and disobedient men, (2) to lead men to a knowledge of their sin, (3) after they are reborn, and although the flesh still inheres in them, to give them on that account a definite rule according to which they should pattern and regulate their entire life. …

We believe, teach and confess that the preaching of the law is to be diligently applied not only to unbelievers and the impenitent but also to people who are genuinely believing, truly converted, regenerated, and justified through faith.

For although they are indeed reborn and have been renewed in the spirit of their mind, such regeneration and renewal is incomplete in this world. In fact, it has only begun, and in the spirit of their mind the believers are in a constant war against their flesh (that is, their corrupt nature and kind), which clings to them until death. (Formula of Concord, Epitome, VI, 1, 3–4a)

Put another way: The Law — loving God with all your heart, soul, and mind, and your neighbor as yourself — doesn’t cease to apply to you once you’re saved. The commandments of the Law tell believers what they ought to be doing as a matter of course. If Christians aren’t doing good works and don’t care, how can anyone tell they are Christians? Indeed, how can they themselves expect to see heaven with such an attitude?

That’s what James was getting at when he wrote that “faith without works is dead” (Jas 2:26). But it’s also what Catholics mean when they speak of justification as a process — one that lasts until God calls us home. If we freely sin and don’t care, we fall into the category of those who “have made shipwreck of their faith” (1 Tim 1:19). But we have the sure promise in 2 Timothy 2:12–13 that “if we endure, we shall also reign with Him” and that “if we are faithless, He remains faithful, for He cannot drny Himself”!

This is the common ground of the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, the breakthrough agreement between Catholics and many Lutherans (though not the Missouri Synod) signed in Augsburg, Germany, on Reformation Day 1999. It declares that the signatories consider its contents to “encompass a consensus on basic truths of the doctrine of justification.”

Its key passage answers both of our key questions of the Christian life: “Together we confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works” (Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, 15).

Does that seem familiar? It should. It’s anchored not only in Ephesians 2:8–9 — the “justification in a nutshell” passage that Lutherans cite so often — but also verses 10 and 11, which Catholics insist must not be forgotten: “For by grace you have been saved through faith; and this is not your own doing, it is the gift of God — not because of works, lest any man should boast. For we are His workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (emphasis added).

One must emphasize that the Joint Declaration speaks of shared “basic truths,” not total agreement. The two faith traditions are still seeking common ground on how we live out our faith, how we know what God expects us to do and how He gives us the grace to do it through Word and Sacrament: in essence, all the remaining points at issue between Lutherans and Catholics.

But it’s clear that Catholics and Lutherans — in two different ways, just as St. John Paul II perceived — agree on what one might call “the circle of eternal life,” one that begins and ends with God.

The circle works like this: God, through Christ’s death for our sins, alone makes our salvation possible. But we have to accept His gift of faith, and we absolutely must live that faith by following God’s commands, lest we lose the Holy Spirit and the salvation that Christ earned for us.

Nevertheless, we cannot follow through and we cannot accept the gift of faith — or, put in the passive form that Lutherans prefer, the reception of faith by us cannot take place — unless God alone gives us the ability to do so. So, in the end, we are totally dependent on God!

The belief that Catholics and Lutherans somehow disagreed on that was, and is, the cornerstone of the typical Lutheran’s mighty fortress against Rome. Once the cornerstone was removed from my wall, the other bricks began to collapse.

Other Similarities

I began to perceive other similarities between Catholics and Lutherans that hadn’t occurred to me before, most notably in the two key ingredients of the Church’s authority: the relationship between Scripture and Tradition and the question of infallibility.

Luther, of course, set the tone for Protestants everywhere with his emphasis on sola scriptura — the Bible as the sole authority. But St. John Paul II changed the tone of the debate in Ut Unum Sint, defining the question in dispute as “the relationship between Sacred Scripture, as the highest authority in matters of faith, and Sacred Tradition, as indispensable to the interpretation of the Word of God.”

Compare that to Article II of the LCMS Constitution, quoted earlier. It’s the same order of primacy! Catholics indeed look first to the Scriptures — but they interpret those Scriptures in the light of the teaching they uphold as directly passed on from the Apostles, the Church Fathers, and the ecumenical councils. And in Missouri’s universe, at any rate, the Lutheran Confessions have the same relationship to Scripture. They define how the LCMS reads and lives its faith.

That harmonizes well with the simple definition of Tradition as “the living and lived faith of the Church” — even more simply, the teachings of the Church. In that light, sola scriptura is nothing more than a phrase or slogan. It can’t be anything else as long as a group of Christians follows a particular set of teachings, whether it comes from Luther, John Calvin, John Knox or John Wesley.

In that case … which side has the better case for its tradition? Lutherans, who kept much of the Catholic tradition but based the rest of their teachings on the interpretations of a handful of sixteenth-century men? Or the Catholic Church, which can do what Luther cannot: cite the Scriptures in defense of its authority to pass on and interpret the faith?

It isn’t that the LCMS in practice denies the connection between Scripture and tradition. It’s a question of which tradition it accepts. The issue of infallibility is much the same. The LCMS believes the Holy Spirit guides its officers and pastors (its Magisterium, if you will) and its triennial conventions (its ecumenical councils) in deciding doctrinal issues.

Again, which has the better scriptural case for its authority? I concluded that Rome had a convincing case — and Missouri, by its own preferred standard, had none. Once I realized that, the other issues between Lutherans and Catholics were much easier to deal with.

There were other areas in which it appeared that Lutheran practice mimicked Catholic reality. Luther may have reduced seven sacraments to two by his own definition. Yet Lutherans hold confirmation, marriage, ordination, confession and absolution (in the corporate sense, anyway) and pastoral care of the sick (parallel to the Catholic sacrament of Anointing of the Sick) in high esteem.

In each, they believe God blesses His people as the pastor proclaims God’s Word. And isn’t that the essence of the “means of grace” that explains the basic act of both Baptism and the Eucharist — the application of God’s Word to visible elements to impart His grace?

Coupled with my new scriptural proofs and my conclusions on Catholic authority, the sacraments proved easier to deal with than I had thought. I had viewed the flow all wrong. The sacraments weren’t obstacles to our reaching God. They were means for God to reach us!

Much the same may be said of Mary and the saints. I didn’t expect those issues to fall as easily as they did. But both are linked to one question: Do Lutherans believe the “communion of saints” unites the saints in heaven and on earth in one body of Christ? And if it does, why would we not seek the aid of the Christians who have gone before?

Lutherans will admit that the saints in heaven, including Mary, pray for the saints on earth. Unfortunately, they don’t believe we can pray to them, asking them to pray for us. But that ignores Paul’s observation that “the eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I have no need of you’” (1 Cor 12:21).

We ask our fellow living Christians to pray for us in time of trouble. The Catholic Church invites us, without demanding it, likewise to seek the prayers of the blessed dead. Christ remains the one Mediator, but He makes use of whatever media He wishes to draw us to Himself — including our fellow members of the Body of Christ.

As for Mary, I found the case for Catholic dogma bolstered by a most unexpected source: Luther himself. Evidence can be found in his writings that he believed in all the Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church: Mary was Mother of God, was perpetually a virgin, was immaculately conceived and assumed into heaven. Most astonishingly, the founder of this tradition that disdains praying to Mary invokes her intercession at the beginning and the end of his commentary on the Magnificat in 1521 — the year he was excommunicated!

It’s quite another thing to equate Mary or the saints with God. Luther was adamant in opposing that thinking — but so is the Catholic Church. Pope Paul VI clarified the point for Catholics when he cautioned that veneration of Mary and the saints must be done within the context of “a rightly ordered faith,” one that looks to Christ as the sole source of salvation and grace.

The Eucharist

This space, of course, is too limited to cover all the Catholic-Lutheran issues, let alone all the evidence I found for the Catholic position. But one more subject needs to be covered. Ultimately for me, it came down to the Eucharist.

The dispute over the sacrifice of the Mass wasn’t the obstacle I expected it to be. The Church does not see it as a repetition of Christ’s sacrifice, as Luther and the Reformers perceived their position, Rather, the Church speaks of the one single sacrifice presented again to us, a re-enactment of Calvary every time we “do this in remembrance” of our Lord. (The late LCMS theology professor Arthur Carl Piepkorn, a key player in the first U.S. Lutheran-Catholic dialogues in the 1960s, wrote of the Eucharist in similar terms.)

That understanding brought me to the transubstantiation issue, the fate of the bread and wine after the Words of Institution. I had come a long way by following the Pope’s advice. I had had to give up very little of my Lutheran way of thinking. But transubstantiation couldn’t be resolved as two different approaches to a common belief. I was back to the diagram my pastor had put on the chalkboard twenty years before: Either the bread and wine are still there — or they aren’t.

So I went to Luther’s 1520 treatise The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, the work that defined his views on transubstantiation and redefined the sacraments. I had been struck by an oddity: Catholics and Lutherans appealed to the same Scripture passages and emphasized a plain, literal reading of the text. There must be something more to Luther’s position.

There was. Luther wrote:

Does not Christ appear to have anticipated this curiosity admirably by saying of the wine, not Hoc est sanguis meus, but Hic est sanguis meus? … That the pronoun “this,” in both Greek and Latin, is referred to “body,” is due to the fact that in both of these languages the two words are of the same gender. In Hebrew, however, which has no neuter gender, “this” is referred to “bread,” so that it would be proper to say Hic [bread] est corpus meum.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, Luther bases his theology on the original Bible languages: Greek and Hebrew, not Latin. But not here. He’s objecting to the Latin translation — the translation of the Church whose authority he was rejecting. He was dismissing the original translation, the Greek, because it agrees with the Latin. And he’s appealing to a different language entirely — Hebrew, which he assumes Christ spoke at the Last Supper (modern scholars believe it more likely was Aramaic) — to undermine the transubstantiation doctrine that he associated with Rome’s supposed corruptions of the faith.

My hands shook as I read that passage for the first time. I thought: But that’s wrong! He can’t do that!

I was back in my professional realm. I don’t know Greek, but I’m a writer, and I can research. I spent the next day ransacking the library and the Internet, finding the exact Greek words and learning how the Greek language treats pronouns.

When I was done, the evidence was overwhelming: In the language used by the New Testament’s divinely inspired authors, Christ’s “this” cannot refer to anything other than “body.” (A straight-across reading of the Greek in an interlinear New Testament reinforces the point: “This is the body of Me.”)My hands shook as I read that passage for the first time. I thought: But that’s wrong! He can’t do that! In other words… . Rome was right, and Luther was wrong. I no longer had a case against joining the Catholic Church. Share on X

In other words … Rome was right, and Luther was wrong. I no longer had a case against joining the Catholic Church.

Prayer for Unity

I took Communion with my wife for the first time less than two months later. Since we’ve been united in faith, we’ve had two more children. God has given me opportunities to defend “the fullness of faith” in print, online and even on television. And God has provided abundantly for our needs, even when economic turmoil cost me my fulltime newspaper career in 2009.

I can’t begin to express the joy of being fully spiritually united with my wife and our family, not to mention all the Catholics whose quiet witness and utter lack of pressure unquestionably were God’s instruments on our way to Rome.

There has been pain, too, and that isn’t an unfamiliar story to Christians who have reconciled with Rome. It’s one thing for Catholics to ask forgiveness for the events of centuries ago. It’s another for Eastern Orthodox and Protestants of all stripes to grant it and to issue their own apologies — to put aside the pain and the polemics and humbly, sincerely, thoroughly explore how it all happened, how the other side thinks and what God is saying to His people in these increasingly faithless days.

St. John Paul the Great and Pope Benedict XVI (his longtime aide, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) have called on Catholics to work for the unity of the Church, to join Christ’s high-priestly prayer that we all may be one. It was the present pope, before his election, who played a critical role in clearing the way for the Joint Declaration on Justification, which made it clear that Catholics agree with Lutherans that we are saved sola gratia (by grace alone) and solus Christus (through Christ alone).

And, as pope, Benedict later taught (Nov. 19, 2008), Catholics can also accept Luther’s sola fide (by faith alone) if the term is rightly understood:

Being just simply means being with Christ and in Christ. And this suffices. Further observances are no longer necessary. For this reason Luther’s phrase “faith alone” is true, if it is not opposed to faith in charity, in love. Faith is looking at Christ, entrusting oneself to Christ, being united to Christ, conformed to Christ, to his life. And the form, the life of Christ, is love; hence to believe is to conform to Christ and to enter into his love. So it is that in the Letter to the Galatians, in which he primarily developed his teaching on justification, St Paul speaks of faith that works through love (see Gal 5:14).

I pray that Rome and Missouri in particular may be led to forgive each other, to look toward God and His Word with truly unbiased eyes and to ask whether they’re meant to remain divided. They share far, far more than they know.

After Blessed John Paul spoke his astonishing words in Denver, I heard Irish recording artist Dana sing the World Youth Day 1993 theme song for the first time. It quickly took root in my heart because of its echo — whether intended or not, I don’t know — of Luther’s alleged “Here I stand” statement at the Diet of Worms. It seems an appropriate way to end this tale:

We are one body, one body in Christ,

And we do not stand alone,

We are one body, one body in Christ,

And He came that we might have life …