This is part of an ongoing series from Ken Hensley. Read previous installments: Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI Part VII Part VIII

Imagine a man who arrives at the airport for his flight.

His suitcase is closed and firmly latched, and yet there are all sorts of items hanging out from the sides—a few socks and a tie here, a shirt sleeve and pant leg there, part of what looks like a sweater.

The lady at the check-in counter says, “Sir, you will need to make sure everything is in your bag before we can check it.”

Hearing this, the man takes a pair of scissors from his pocket and proceeds to carefully cut around the outside of his suitcase, trimming away everything he wasn’t able to fit inside. He finishes, looks at the attendant and says, “OK, now everything is in my suitcase.”

The atheist is like this man. He insists that he can explain every aspect of the universe and our experience in it in terms of his naturalist-materialist worldview, where nothing exists but particles interacting according to strict physical laws.

He insists that everything can be “accounted for,” that everything “fits.” And lo and behold, it turns out that everything does fit. Because whatever doesn’t fit, he simply trims away. If it doesn’t fit into his philosophical suitcase, it doesn’t exist. It’s illusion.

Thus, consistent atheists admit—even insist—that it’s pure illusion to think that we human beings are “special,” that we possess unique value in the eyes of a god who doesn’t exist.

It’s an illusion to believe that “Right” and “Wrong” are anything more than words we use to describe what we approve or disapprove—either individually or as groups.

It’s an illusion to talk about people possessing “unalienable rights.” Whatever rights we have are rights we grant to one another.

It’s an illusion to believe that life has transcendent meaning.

Even consciousness, and our sense of personal identity—of being “somebody” rather than “nobody”—is an illusion generated by electrochemical processes in the brain.

It’s a “bag of tricks” says Daniel Dennett.

But it doesn’t stop there. Another illusion is the illusion of our being agents with the ability to choose: free will.

The Common and Intuitive Conception

Most of us would say that we act “freely” to the degree that our choices are not determined by forces outside our own will.

Philosophers refer to this view as “libertarian free will.” This is our common sense understanding of free will, and it’s rooted in our common sense experience. Each of us is simply aware—immediately and intuitively—that we are agents with the power to choose. I can choose to eat the apple or the orange, to walk around the block or up and down the street, to watch this movie or that. I am free.

And while my choices will always be “influenced” – sometimes powerfully influenced – by forces internal and external, to the degree that my choice is not determined by those factors, to the degree that I am able to act or not act, to act one way or another, we describe those acts as the “free” acts of a free agent.

Even if I like apples better than oranges, I could still “choose” to eat the orange. Even if there is a gun to my head insisting that I walk around the block, I could still “decide” to walk up and down the street and take the consequences.

Now, this is how we experience free will. And even those who hold to a hard determinism in the course of their normal lives act as though they believed in this view of free will.

It’s important to point out that atheists readily admit this.

In fact, popular atheist author Sam Harris complains that “people find the idea of libertarian free will so intuitively compelling” that it’s hard to even get them to “think clearly about determinism.”

Atheist philosopher of mind John Searle admits that this common notion of free will is so inescapable that even if it is an illusion we would have to live as though it were not!

It also happens to fit the Christian-theistic worldview:

God created man a rational being, conferring on him the dignity of a person who can initiate and control his own actions. . . . Freedom is the power, rooted in reason and will, to act or not to act, to do this or that, and so to perform deliberate actions on one’s own responsibility (Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraphs 1730 and 31).

Free Will and Naturalism

But what happens to free will if the universe is what the philosophical materialist says it is?

Physical systems are by their nature deterministic. Drop a pin on the floor and it will go precisely where it must go, given all the physical conditions in play at the time. Fire a rocket into the air. The same. Physical systems operate according to strict physical laws. And even if one wishes to talk about “quantum uncertainty” along with determinism, one will still not be talking about “free will.”

Well, according to the atheist-materialist worldview, our entire universe represents one massive, inescapably deterministic closed system of causes and effects. And you and I are products of that one massive, inescapably deterministic closed system of causes and effects. In other words, the “machine” we call the physical universe includes you and me and everything about us.

The logical implication: “free will” is an illusion.

Again, this is something consistent atheists do not shy away from admitting and, as I said, even insisting on.

As atheist philosopher of mind John Searle writes:

[W]e are inclined to say that since nature consists of particles and their relations with each other, and since everything can be accounted for in terms of those particles and their relations, there is simply no room for freedom of will . . . (Minds, Brains and Science, pp. 86-87).

Atheist Sam Harris has no problem openly declaring that free will is “an illusion.” He writes:

Human thought and behavior are determined by prior states of the universe and its laws . . . . We are driven by chance and necessity, just as a marionette is set dancing on its strings (The Marionette’s Lament).

Given their mechanistic view of the world, the conclusion of these men would seem to follow inescapably. Whether they choose to describe their position as “hard determinism” or “soft determinism,” if “everything” can be accounted for in terms of particles and their relations, if even human thought and behavior are “determined” by prior states of the universe and its laws, including prior mental states, then clearly your thoughts and ideas, your reasoning processes and resulting choices, being a part of “everything,” are determined as well.

So much for “free will.”

Why talk and write and debate?

Of course one wonders exactly why Searle believes his ideas are worth sharing with his students at Berkeley or being written down in a book—given that according to his own statements, every one of them can be accounted for in terms of particles and their relations.

And why does Sam Harris want to make videos and speak all over the place when, according to his own worldview, every single one of his thoughts and ideas, the contents of his lectures and books and articles, have been entirely “determined by prior states of the universe and its laws.” Mechanically determined.

When Harris says, “free will is an illusion,” by his own admission he is speaking as a mere marionette “set dancing on its strings.”

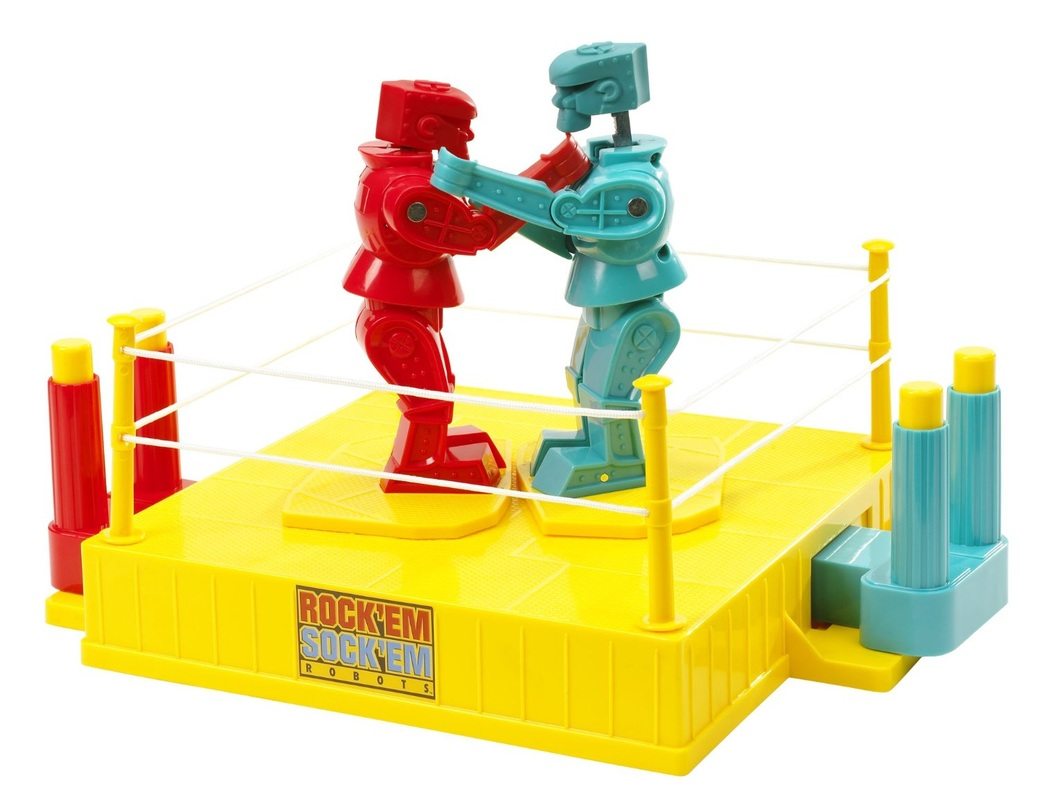

Searle and Harris are a pair of Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Human Robots. They cannot say anything other than what they are saying. And their hearers cannot respond in any way other than how they respond.

So why are they saying anything?

Materialism and Moral Accountability

Which leads to the issue of moral accountability. How can a person be held “morally” accountable when everything he or she does is determined by prior states of the universe, particles, and so forth?

Harris rises to the occasion and asserts that we should cease entirely talking about accountability in “moral” terms.

He insists, for instance, that Ted Bundy had no more choice in whether or not he would kidnap, torture and murder young women than a rattlesnake has in whether or not it will strike at someone who crosses its path. Like the snake, Bundy did only what he had to do, given his nature. If we understood this, Harris explains, we wouldn’t throw around terms like “evil” and “guilty” and all the rest. We would just lock Bundy away to protect the innocent, as we might a rattlesnake or any other dangerous creature.

I’m sitting here trying to imagine how Sam Harris, as Ted Bundy’s defense attorney, might deliver his closing argument:

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, as you move from this courtroom to deliberations, I ask you to keep a few scientific facts in mind.

First, remember that my client is nothing more than a marionette dancing on his strings. Given the prior state of the universe and the laws of nature, he did only what he had to do. Whether driven by chance or necessity, he had no choice in whether or not to torture and murder those young women.

Second, keep in mind that you also are nothing more than twelve marionettes dancing on your respective strings, and that the way each of you votes will be determined entirely by prior states of the universe and the laws of nature, particles and their relations and so forth.

In fact [now addressing the judge] your honor, when the verdict comes down and you pass sentence on my client, your sentence also will also be that of a mere marionette dancing on its strings, entirely determined by prior states of the universe, particles and their relations, etc.

In short, everything taking place in these proceedings is and will be determined—mechanically determined, as determined as the movement of pistons in the combustion engines in our cars—by the massive material machine within which we are nothing more than cogs.

In the light of this scientific reality, I ask you, your honor, how is it possible for my client to obtain an impartial verdict?

Evangelism and Free Will

A rabbi once said, “The theist has to explain unjust suffering; the atheist has to explain everything else.”

Evangelism with someone who doubts or denies the existence of God can move along a number of lines. Depending on the person I’m talking to, I might decide to share the story of my own conversion to Christ and experience as a Christian. I might decide to present rational arguments for the existence of God and the truth of the Christian worldview.

I might decide to share the story of Christ’s life, teaching, miracles, death and resurrection — and the evidence for these events having actually happened. I might talk about the apostles and the early Church, or the saints, or the happiness that knowing God and knowing your purpose in life brings.

But it doesn’t hurt, with some, to also perform what I refer to as an “internal critique” of the atheist-materialist worldview. This is where I want to step into my friend’s worldview and talk about its implications. If it’s fair game for the atheist to examine my worldview as a Christian, surely it’s fair game for me to examine his — and in this case to point out that my friend cannot, on the basis of what he says is true of the universe in which we live, account for human freedom.

For him, nothing exists but a massive closed system of physical causes and effects.

Because of this, he cannot account for his thoughts, ideas, desires, intentions, hopes, plans, memories — even the argument he’s presenting to me — being anything more than an expression of that closed system of physical causes and effects. According to him, it is as determined that he not believe in God as it is that I believe in God.

According to his worldview, debate is meaningless.

Neither can he account for moral responsibility. Holding someone “morally accountable” doesn’t make any sense in a materialist universe. It doesn’t make any sense to “blame” people for the bad they do and it doesn’t make any sense to “praise” them for the good they do. Both, after all, are mere marionettes dancing on their strings.

Sometimes it’s good evangelism to assist an atheist in facing the logical implications of his or her worldview.

When your atheist friend read Dawkins’ The God Delusion and decided that atheism made sense and maybe even began to mock Christians for their faith in God, he might not have considered that renouncing belief in God he would also have to renounce a number of other beliefs: his belief in his own freedom, his belief in moral accountability, in short, his belief that he is anything more than a biochemical machine, a Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Human Robot.

Up Next: How I Evangelize Those Who Doubt or Deny the Existence of God, Part X